As I was reading Daniel's post about artificial intelligence (and enjoying that clip from 2001: A Space Odyssey), it made me think of how computers don't just puzzle us with conundrums about the nature of thought; they SCARE us. And you don't need that big red eye-ball to get freaked out by our microchip masters. They frighten us not just because of what they can do, their feats of memory and manipulation, but because of the way

we have become so dependent upon them. They are so integrated into our lives. They are so universal, so catholic. (The word "catholic" means "universal" and only later became a proper noun naming the Catholic church).

|

| we see through a glass, pixely |

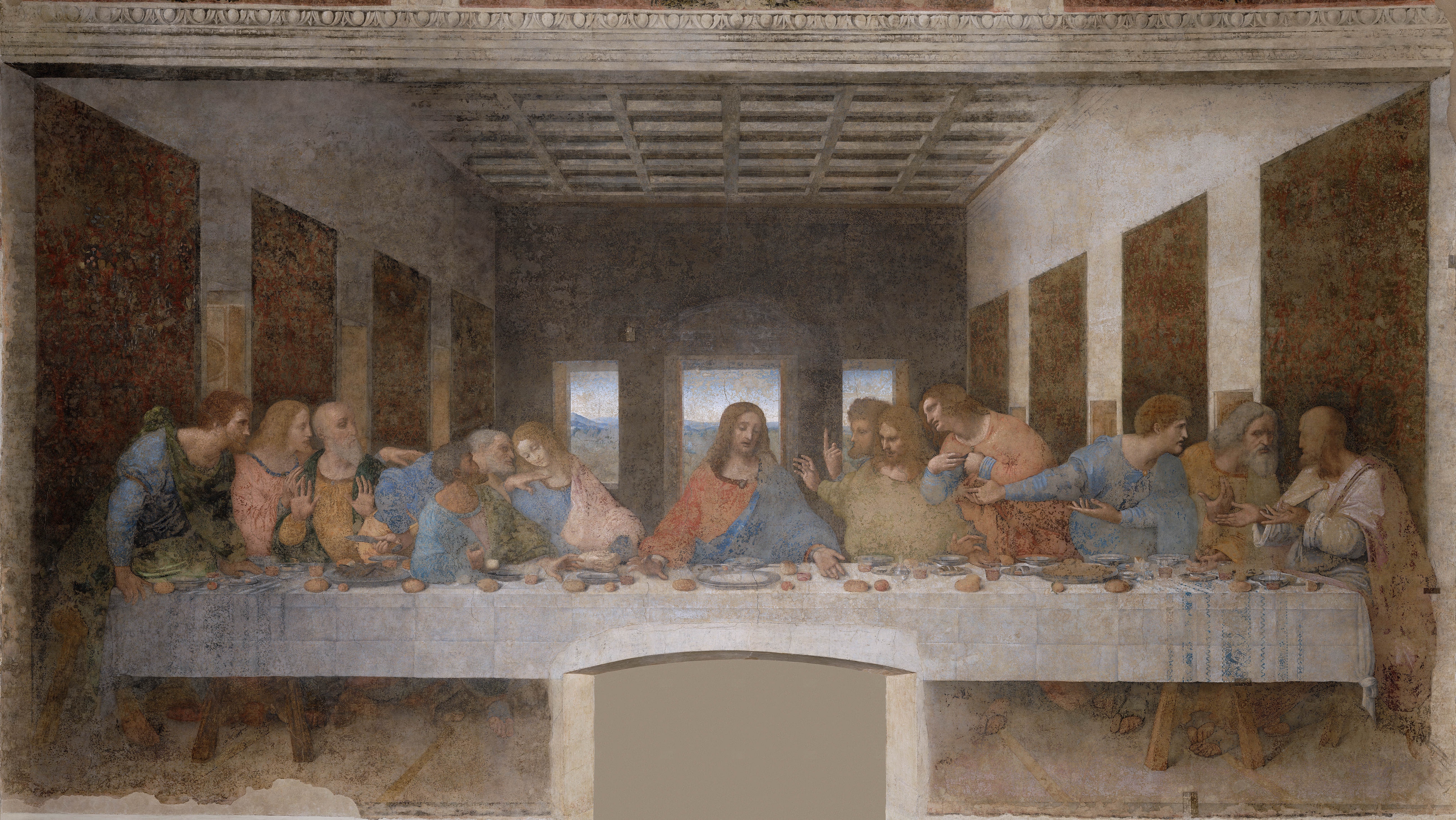

Computers are catholic (not Catholic), and that is a scary thing. I make this odd comparison because I want to link computing to the Renaissance and to the ways that those living in that time underwent a radical change in perspective. The culture of Western Europe in the late middle ages was completely dominated by the Catholic church. It was an institution that ordered their lives, and their thinking. (This was not always an oppressive thing as it is sometimes stereotyped as being. The Catholic church was a marvel of efficiency and sustained literacy over the centuries...).

Side story. I'm directing a play right now, and one of the actors is a producer for BYU Television, and she is looking for a family that they can feature in one of those "let's take your technology away for a week and watch you all go into withdrawal" kinds of things. I told her how wired my family is, how my wife and I sit next to each other in bed tapping at our laptops and sending each other instant messages even though we are seated six inches from one another. That sort of thing. She started salivating, like the Burton clan is perfect for one of these expose-like features condemning the overlords of technology.

|

| religion orders lives |

|

| computing orders our lives |

Well, how would you do if the BYU TV people came to you and asked you to park your phones, your computers, and stay away from all screens for a week or more? That's right, you'd get the shakes and start foaming at the mouth. I'm doing that right now just thinking about such a media fast. (Part of me secretly wants to have that media fast, I confess...)

What's my point? Substitute our world-o-tech for the world of Catholicism at the end of the middle ages. Like that religious institution, computing and technology have become institutionalized in our lives. It gives us order, routine, and an orientation to our time and our perspectives. I'm liking this comparison more and more. Computers and technology are the modern day counterparts to medieval Catholicism. Heck, I think some people are more devoted to their cell phones than generations of Catholics were to their saints or rituals.

So, along comes some people who challenge the basic premises of Catholicism. People like Copernicus and Galileo, who have the temerity to say that the map of the cosmos is drawn wrong. All wrong. Earth isn't in the center; the sun is. You just cant take away that Ptolemaic worldview from people cold turkey. It's like the teenager who text messages in her sleep or under the table. Take her cell phone away and what do you have? Someone who reads and knits for the poor? No, you have a freaked out teenager who is going to snap at you like a junkyard dog.

I hope you see where I'm going with this. Today we are so immersed in change and in one new world being opened up to us after another, we forget how hard it is to shift gears from a very stable, constant, and reliable worldview to another one.

Computing and tech are a worldview. We mostly like it, but like all worldviews, we don't sense how much it controls our thinking and feeling unless it is challenged.

So who are the Galileos of today? Is anyone challenging the status quo?

Andrew Keen is. And he is doing so in terms of another concept from the Renaissance: utopianism. He says Web2.0 is a technological utopianism that just doesn't cut it. We've been trapped in the romance of the new tools, but losing sight of what real knowledge or creativity is all about.

Why would anyone bother challenging our progressive computing world? What worldview is there to supplant or transcend it?